Building a Custom Qt Stack on Linux

Building Qt on Linux isn’t just a box-checking exercise. It’s a strategic decision that can shape your entire embedded stack. In this post, we break down why you might need to build Qt yourself and the major paths you can take to get there.

Why Build Your Own Qt

Most of the time, your distribution’s own Qt package offers enough for the task. Plus, it brings the benefit of having a tested build and debugging symbols that can be installed when needed. If you happen to need something different, you can interact with your distribution’s Qt maintainers to see whether your change fits. If it does, it is a win-win situation and a contribution to the open source ecosystem.

But, there are times when using your own distro might not be appropriate. You might need to build Qt with a particular configuration option enabled/disabled, for example. Or you might need a particular version for some other compelling reason. You might even simply want to learn how to do it.

If any of these fit your situation then this blog post should give you a good base to start with this experience. Be ready to use CPU time and iterate!

Approaches to Qt Sources

If you’re going to build Qt, the first thing you need is its source code. There are two ways to get it: via git or by downloading tarballs. Yes, tarballs – plural. Here’s why. Qt can be compiled in two main ways. 1. The “single” approach – one massive checkout or tarball containing all the source code for every Qt module. 2. The submodule approach – building each Qt module separately, piece by piece.

Each method has its pros and cons, so let’s break it down.

Single Approach

With the single approach, there’s one big codebase. This is great for building documentation, because all modules are present and cross-references between modules work automatically. You also don’t need to manually tell the build system where each submodule is – it’s all there.

The downside? If something goes wrong during the build, restarting can feel painful. Even small mistakes can force the build to redo a lot of steps because the build system checks everything again.

Submodule Approach

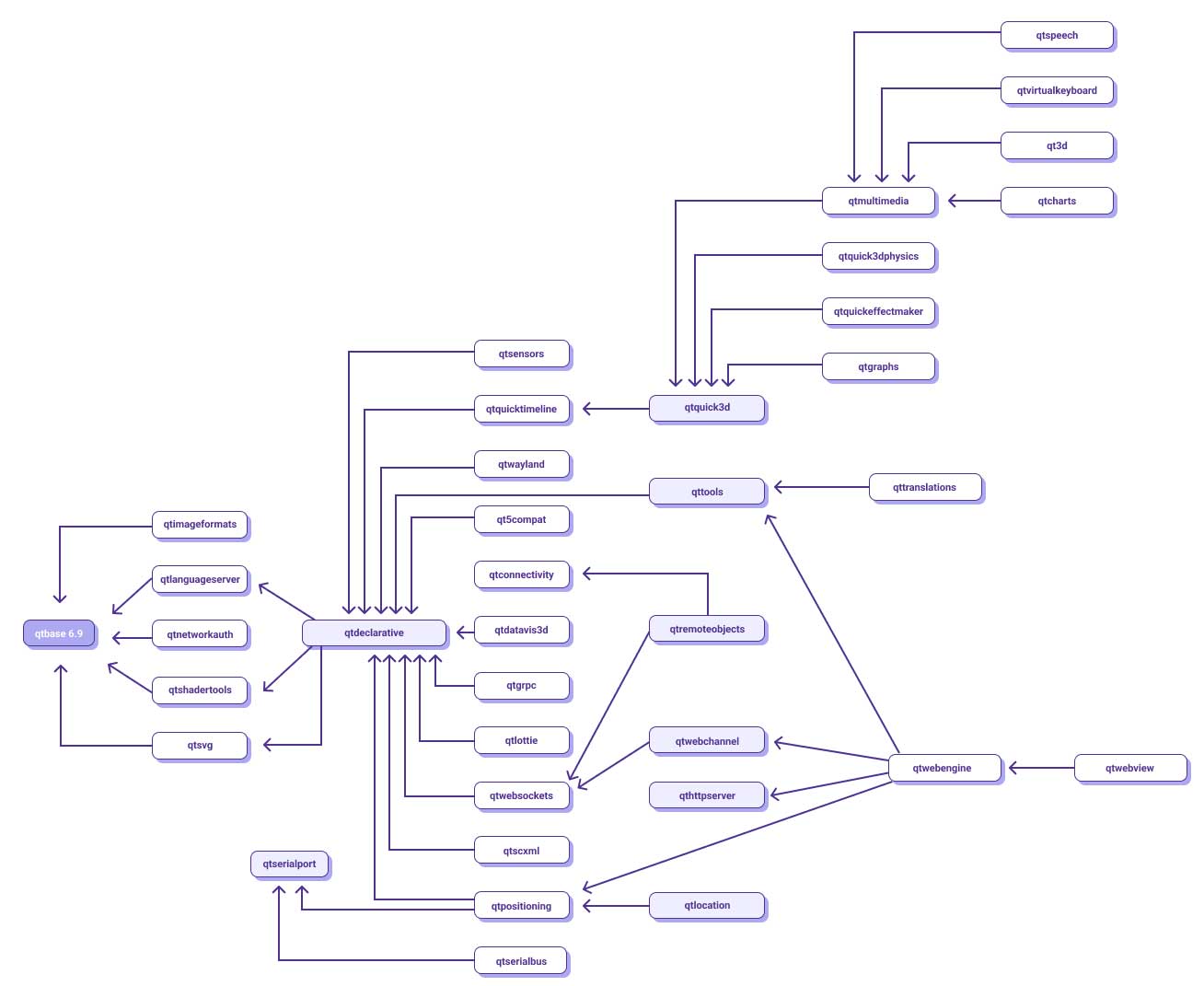

The submodule approach is a bit trickier. You build Qt module by module, in a particular order, and make sure each finished piece is available to the other modules as you go. Yes, this requires knowing which modules depend on which.

This is something I did a lot while building Qt for Debian, so let me use this image:

Based on Debian’s Qt/KDE team dot file.

You might think “That sounds like a lot of submodules!” And you’d be right.

But there’s a silver lining: you only build what you need. For example, a pure Widgets UI? You only need Qt Base. A QML interface? You’ll need Qt Declarative, with optional modules like Qt ImageFormats or Qt NetworkAuth.

Another big advantage of the per-submodule approach is patching. Need to tweak something in Qt WebSockets? As long as you don’t break API/ABI, you can simply rebuild just WebSockets and install. There’s no need to rebuild the entire Qt stack (assuming you’re working with shared libraries).

Git vs. Tarballs

Qt isn’t a “run CMake and go” kind of project. Even if you grab the source from git, there’s internal tooling that must be run to generate extra files, like the ones defining the build version. The Building Qt 6 from Git wiki explains this in detail and walks through the single-approach build process.

The tarballs approach might feel a bit old-school these days, but they’re still handy. Maybe your network restricts git access. Or the build system was set up to handle tarballs instead of git.

Qt tarballs are available at Qt’s official releases in both single and submodule forms. As of today, the single tarball for Qt 6.10.2 compressed with xz clocks in at 1.2 GB — yes, it’s huge. By contrast, the Qt Base submodule is only 48 MB, which can make a big difference if you only need part of Qt.

Configuring Qt Base

Qt Base is the first submodule to be built, and it effectively sets up the whole build. This is true whether you’re using the single approach or the per-submodule approach.

The Wiki lists a minimal set of packages required to build Qt, but as always, it depends on which features you want. Fewer features mean less code to compile and a smaller attack surface — but also less functionality. At a minimum, you’ll need a compiler and CMake. Beyond that, the rest of the build dependencies are based on your configuration options.

So, how do you figure out your options? The answer is on the config_help.txt file. It explains the parameters you can pass to the helper configure script that comes with the source.

And you have lots of options. Some are architecture-specific, while others control general behavior. For example, need OpenSSL in your network stack? Pass -ssl. Don’t use the Network module but your device has a resistive touchscreen with tslib? Pass -tslib.

Running configure with no parameters will use reasonable defaults, which is a good starting point. From there, you can refine what you really do and don’t need and pass additional options accordingly.

Once that’s done, it’s time to call CMake. The configure script even gives you helpful hints before you proceed.

Qt is now configured for building. Just run 'cmake --build . --parallel'

Once everything is built, you must run 'cmake --install .'

Qt will be installed into '/usr/local/Qt-6.10.2'

To configure and build other Qt modules, you can use the following convenience script:

/usr/local/Qt-6.10.2/bin/qt-configure-moduleNotice how it also mentions the qt-configure-module script? That’s because we’re building Qt Base from its submodule tarball. Once Qt Base is installed, the next step is to grab the tarball for the module you want to build next, say the Qt LanguageServer, extract it and run qt-configure-module following the same process.

Here’s an example using Qt LanguageServer:

lisandro@myserver:~/Downloads/qt/qtlanguageserver-everywhere-src-6.10.2$ /usr/local/Qt-6.10.2/bin/qt-configure-module .

'/usr/local/Qt-6.10.2/bin/../libexec/qt-cmake-private' '-DQT_INTERNAL_CALLED_FROM_CONFIGURE:BOOL=TRUE' '.'

-- The CXX compiler identification is GNU 14.2.0

-- The C compiler identification is GNU 14.2.0

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info - done

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++ - skipped

-- Detecting CXX compile features

-- Detecting CXX compile features - done

-- Detecting C compiler ABI info

-- Detecting C compiler ABI info - done

-- Check for working C compiler: /usr/bin/cc - skipped

-- Detecting C compile features

-- Detecting C compile features - done

-- Performing Test CMAKE_HAVE_LIBC_PTHREAD

-- Performing Test CMAKE_HAVE_LIBC_PTHREAD - Success

-- Found Threads: TRUE

-- Performing Test HAVE_STDATOMIC

-- Performing Test HAVE_STDATOMIC - Success

-- Found WrapAtomic: TRUE

-- Force setting build type to 'Release'.

-- Configuration summary has been written to /home/lisandro/Downloads/qt/qtlanguageserver-everywhere-src-6.10.2/config.summary

-- Configuring done (1.5s)

-- Generating done (0.0s)

-- Build files have been written to: /home/lisandro/Downloads/qt/qtlanguageserver-everywhere-src-6.10.2Bonus Track 1: Debian’s Qt Packages

It’s interesting to see how distributions configure their Qt builds. I was a Debian Qt maintainer for many years so we’ll use Debian as an example. Ubuntu does things very similarly. (You can always check your own distro to see their approach.)

Debian packages use a special file called rules to configure and build code. For Qt 6 Base, you can find it here. The large snippet below shows how the override_dh_auto_configure section sets up the build:

override_dh_auto_configure:

dh_auto_configure -- \

--log-level=STATUS \

-DCMAKE_LIBRARY_PATH=$(DEB_HOST_MULTIARCH) \

-DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=/usr \

-DINSTALL_BINDIR=lib/qt6/bin \

-DINSTALL_LIBDIR=lib/$(DEB_HOST_MULTIARCH) \

-DINSTALL_LIBEXECDIR=lib/qt6/libexec \

-DINSTALL_ARCHDATADIR=lib/$(DEB_HOST_MULTIARCH)/qt6 \

-DINSTALL_EXAMPLESDIR=lib/$(DEB_HOST_MULTIARCH)/qt6/examples \

-DINSTALL_DATADIR=share/qt6 \

-DINSTALL_DOCDIR=share/qt6/doc \

-DINSTALL_SYSCONFDIR=/etc/xdg \

-DINSTALL_INCLUDEDIR=include/$(DEB_HOST_MULTIARCH)/qt6 \

-DINSTALL_TRANSLATIONSDIR=share/qt6/translations \

-DINSTALL_MKSPECSDIR=lib/$(DEB_HOST_MULTIARCH)/qt6/mkspecs \

-DINSTALL_PUBLICBINDIR=bin \

-DQT_BUILD_EXAMPLES=ON \

-DQT_INSTALL_EXAMPLES_SOURCES=ON \

-DFEATURE_accessibility=ON \

-DFEATURE_cups=ON \

-DFEATURE_dbus_linked=ON \

-DFEATURE_directfb=OFF \

-DFEATURE_doubleconversion=ON \

-DFEATURE_fontconfig=ON \

-DFEATURE_freetype=ON \

-DFEATURE_glib=ON \

-DFEATURE_gtk3=ON \

-DFEATURE_harfbuzz=ON \

-DFEATURE_icu=ON \

-DFEATURE_jpeg=ON \

-DFEATURE_libproxy=ON \

-DFEATURE_mimetype_database=OFF \

-DFEATURE_pcre2=ON \

-DFEATURE_png=ON \

-DFEATURE_reduce_relocations=OFF \

-DFEATURE_relocatable=OFF \

-DFEATURE_rpath=OFF \

-DFEATURE_sql_mysql=ON \

-DFEATURE_sql_odbc=ON \

-DFEATURE_sql_psql=ON \

-DFEATURE_sql_sqlite=ON \

-DFEATURE_ssl=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_jpeg=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_libb2=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_pcre2=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_png=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_proxies=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_sqlite=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_xcb_xinput=ON \

-DFEATURE_system_zlib=ON \

$(extra_cmake_args)A few points stand out:

- DEB_ variables handle Debian-specific paths and multiarch support

- CMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=/usr ensures Qt installs as part of the packaging system, rather than in /usr/local like a manual build

- FEATURE_foo flags explicitly enable features, making it clear exactly what the maintainer wants included

On Debian, Qt 6 is built by submodules, which makes builds more manageable. Each commit triggers a clean build from scratch. If we tried the single-tarball approach, a build failure would force us to recompile everything due to the way Debian build servers work.

Submodules let maintainers easily deal with changes/errors without breaking the whole ecosystem. The trade-off? Documentation can’t be fully cross-referenced like the upstream docs, though it’s still complete.

Another key difference between Debian builds versus other builds is that Debian builds aren’t meant to produce standalone binaries to ship outside the packaging system. If your application tries to bundle QML plugins, it will fail because the relevant CMake files are removed on purpose. This keeps the build lightweight and avoids unnecessary runtime dependencies, which is a big deal when supporting Debian’s wide range of architectures.

Bonus Track 2: Qt in Yocto

Yocto shares Debian’s submodule approach, but with a significantly different goal: building device images tailored exactly to the hardware and use case. Software engineers typically include only the Qt modules needed for the device, cutting unused features to reduce footprint and minimize potential attack surfaces.

What This All Means

Building Qt is a huge task, but not impossible. It takes patience to learn the ropes (and compile!), so only dive in if your project truly requires it. Consider your options carefully — single vs. submodules, git vs. tarballs, full vs. minimal features — before you start. With a little planning, you can build exactly the Qt you need without overcomplicating things, whether for a distro, a custom device or a specialized application.